Puerto Rico Can Reach Its 100% Renewable Energy Goal by 2050

Frequent and extreme weather events. Record-setting power outages. High energy costs. These are some of the galvanizing forces that unite the people of Puerto Rico in their commitment to achieve a more resilient, reliable, affordable energy system.

Puerto Rico hit a deadly record in 2017, when back-to-back hurricanes destroyed around 80% of the island's electric grid. This was the longest blackout in U.S. history—taking 328 days to get power fully restored—and resulted in more than 3,000 lives lost.

In the face of these challenges, the people of Puerto Rico want to rebuild differently. In 2019, they passed Act 17, committing to reach a 100% renewable energy system by 2050. With billions of dollars in funding, the question is where and how to invest, while remaining true to their values and priorities.

The Puerto Rico Grid Resilience and Transitions to 100% Renewable Energy Study (PR100) is a two-year study—led by the U.S. Department of Energy's Grid Deployment Office with funding from the Federal Emergency Management Agency—that leveraged and integrated dozens of best-in-class models and in-depth analyses from researchers across six DOE national laboratories: the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (which led the study), along with Argonne National Laboratory, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, and Sandia National Laboratories.

"We live in remarkably challenging times. It is collaborative efforts such as PR100 that show NREL answering those challenges in inspiring ways,” said NREL Director Martin Keller. “What I find exhilarating about the PR100 study is that it validates NREL's approach to such all-encompassing community visions—it is a result of our extensive dialogue with the people who will bring these ideas to life."

Voices Across Puerto Rico Drive PR100 Focus

The research team knew that Puerto Rico's priorities needed to drive the direction of their research activities. So they partnered with the Hispanic Federation in Puerto Rico throughout the study to advise on and facilitate the stakeholder engagement strategy, including a PR100 Community Engagement Tour with visits to communities across Puerto Rico—from Mayaguez to Vieques—and roundtables with local businesses, the agricultural sector, people with disabilities, workforce experts, and philanthropists.

“These sessions were intentionally designed to be accessible to as many people as possible, which meant traveling across Puerto Rico, providing English and Spanish interpretation, and hosting some sessions online,” explained NREL’s Robin Burton, the study’s co-principal investigator. “It helped us understand how residents and organizations have been impacted by the energy system and what they want and do not want to see in the future. What we heard is already informing implementation.”

In addition to this community engagement tour, the PR100 team also established an advisory group—which intentionally represented diverse perspectives—and a steering committee to help formulate the scenarios they wanted in the study and provide data and feedback throughout the process.

“No one can say 'I did not know about [PR100]' or 'I was not a part of it',” remarked Eduardo Bhatia, a former Puerto Rico senator who sat on the advisory group. “Anyone who wanted to be part of it was a part of it.”

NREL researchers and the project team worked closely with the advisory group during the first six months of the study to define scenarios to model based on the stakeholder priorities:

- Energy access and affordability

- Reliability and resilience (under both normal and extreme weather conditions)

- Siting, land use, environmental and health effects

- Economic and workforce development.

NREL and the other national laboratories have the right combination of modeling tools that incorporated those priorities into the renewable energy technology analysis.

“We needed to know what changes to the transmission and distribution grid infrastructure would be needed to achieve 100% renewable energy, with significant adoption of residential rooftop solar paired with battery energy storage,” said NREL’s Murali Baggu, the study’s co-principal investigator. “So, we explored a mix of solar photovoltaics, battery energy storage, wind energy, other renewable generation and infrastructure evolution options—both at the grid scale and for individual buildings—that is most achievable, cost-effective, and resilient against disruptions.”

Three Scenarios Reflect Concentrated vs. Widespread Solar-Plus-Storage Deployment

Three possible pathways (or "scenarios") were identified by the PR100 team as viable for a future energy system that is resilient for the most remote communities, obliging of land-use interests, and supportive of distributed and local ownership.

“The level of Puerto Rico’s reliance on distributed energy generation will affect policy and investment strategy over the coming years,” said Nate Blair, NREL’s PR100 technical lead. “Exploring the implications of various levels of distributed generation—through scenarios—helps answer questions about trade-offs and possible outcomes.”

Six national laboratory models were used in concert to produce each scenario, including NREL's dGen and Engage (capacity expansion), PRAS (resource adequacy), and SIENNA (production cost) tools.

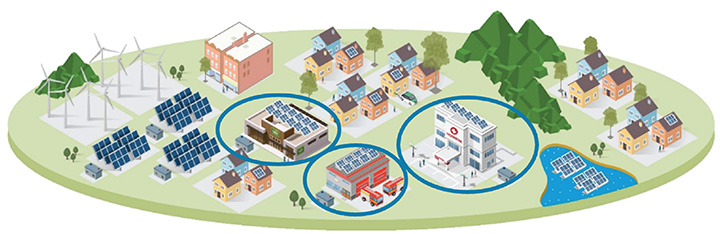

Scenario 1—Economic

Researchers used NREL’s dGen model to calculate the likely adoption of distributed solar and storage based on the financial savings and value of backup power to building owners and prioritized for critical services (circled) through installation and use of distributed energy resources.

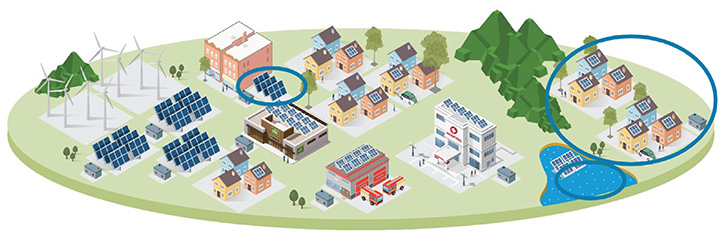

Scenario 2—Equitable

Rooftop solar and storage adoption was expanded beyond Scenario 1 to include remote and low- and moderate-income households.

Scenario 2 modeled remote municipalities (in green, building on Scenario 1 by expanding the number of rooftop solar and storage systems deployed to very low-income households and households in remote areas. Households earning 0%–30% of area median income were considered to be low-income. Remote areas can be defined by outage duration after a major disruption such as Hurricane Maria, typical outage durations in the absence of a storm or other disruptive event, and other outage metrics.

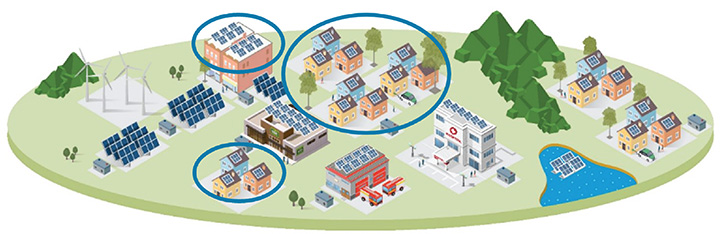

Scenario 3—Maximum

Rooftop solar and storage is added to all suitable rooftops to meet critical loads. This deploys enough rooftop solar and storage to meet the critical loads for all buildings, resulting in extensive deployment across Puerto Rico.

For each of these scenarios, four variations were created based on land usage and energy loads, resulting in 12 total scenarios for stakeholder consideration. Two land-use variations—Less Land and More Land—were defined to assess developable area for utility-scale solar and wind, based on input that preservation of agricultural land is a high priority. Both variations exclude roadways, water bodies, protected habitats, flood risk areas, slopes greater than 10%, and agricultural reserves from developable area; Less Land also excludes agricultural land defined by the 2015 Puerto Rico Land Use Plan.

Due to the uncertainty around electric load (demand) projections, two electric-load variations were defined: Mid case and Stress. The Stress variation increases over time, capturing uncertainty if loads do not decrease and ensuring decision makers do not under plan.

Technically Feasible Options Need System Upgrades, Investments

PR100 contains one foremost conclusion: While it is technically feasible for Puerto Rico to transition to 100% renewable energy by 2050, significant system upgrades and investments—guided by meaningful community participation—are needed.

The current power system is fragile and has been underperforming and under invested. Correcting the situation will require infrastructure and operational improvements no matter which path is chosen. The benefits of these changes include improvements in the safety, security, health, and economic opportunity of Puerto Rico. Regardless of renewable energy goals, the grid needs immediate investments to meet reliability standards. Even more investments are needed to handle the transition to renewable resources.

The future energy system in Puerto Rico can be affordable for the most vulnerable customers, resilient for the most remote communities, obliging of land-use interests, and supportive of distributed and local ownership. It can recover quickly from outages and stand up to the hardest storm surges—and could become a model of successful renewable energy integration for other islands and energy burdened areas.

Specific data and findings related to these scenarios and topics were presented to the public in the PR100 webinar on February 7, 2024.

Comments (0)

This post does not have any comments. Be the first to leave a comment below.

Featured Product